A zine I almost made a couple times some decades apart...

/I wrote this during the pandemic and never printed it. My error is your digital clutter. I hope you like Google Docs.

I wrote this during the pandemic and never printed it. My error is your digital clutter. I hope you like Google Docs.

zinerino

Hello friends, if you’re out there. I suppose hello if you’re not, too. It’s been a while since I’ve taken advantage of this platform but just finished this poem and wanted to share it here. I hope you enjoy it.

Thirteen Lashings

Forgiving myself for getting

into a scrape

over a battery operated Bigfoot

truck with a kid named Jesse

not my first transgression

but the first one I can

but my hands to.

Forgiving myself for throwing

tantrums nearly nightly,

my dad, the apple of my ire.

Blame instead

Ronald Reagan

cigarettes in shopping malls

and undiagnosed disorders.

Forgiving myself for swearing

on the playground

for attention

for affection

and disappointing my mom

when she got the call

from the school.

Forgiving myself for swearing

or pledging

or making an oath

to a country

whose history

and secret

and not so secret

dealings

I had yet to understand.

Forgiving myself for cheating

on a worksheet

we’d reviewed in class

during lunch,

my need to be good enough

far too frail

for one wrong response.

Forgiving myself for stealing

an incredible magnet

to which I was drawn

like iron

when Mr. Bechetti was away

and disppointing my mom

when she got the call

from the school

Forgiving myself for imagining

the people in my life who may put eyes

on these words

and deciding to write

this next part

anyway:

Forgiving myself for being

in the church

instead of in

diligent pursuit

of pussy.

Forgiving myself for believing

all the things

they told me

about myself

and others

and pleasure

and punishment.

Forgiving myself for believing

all the things

they told me

about myself

long after I stopped believing

all the things

they told me

about everything else.

Forgiving myself for being

in the majority

on nearly every measure

and believing

all the things

they told me

about others

based on the fluke of my birth.

Forgiving myself for now considering

quitting

getting up from the computer

as I pause

to contemplate

the blemishes yet unnamed.

We’ve reached a part of the timeline

where I might have been

expected to know better,

to not cause pain.

Forgiving myself for considering

omitting

what I’d just as soon

privately absolve

if such a thing is possible

and if so in what

cosmology?

Forgiving myself for creating

this exercise in self-love

and flagellation,

in performative contrition

and painful confession.

As a rabid devourer of podcasts, I’ve long thought it weird that a) I don’t have one and b) I’ve never been on one. Well, dear internet blog readers, I’m happy to tell you that, as of late yesterday, the latter is no longer true. I was so happy to be a guest on the Overtired Podcast. Please enjoy!

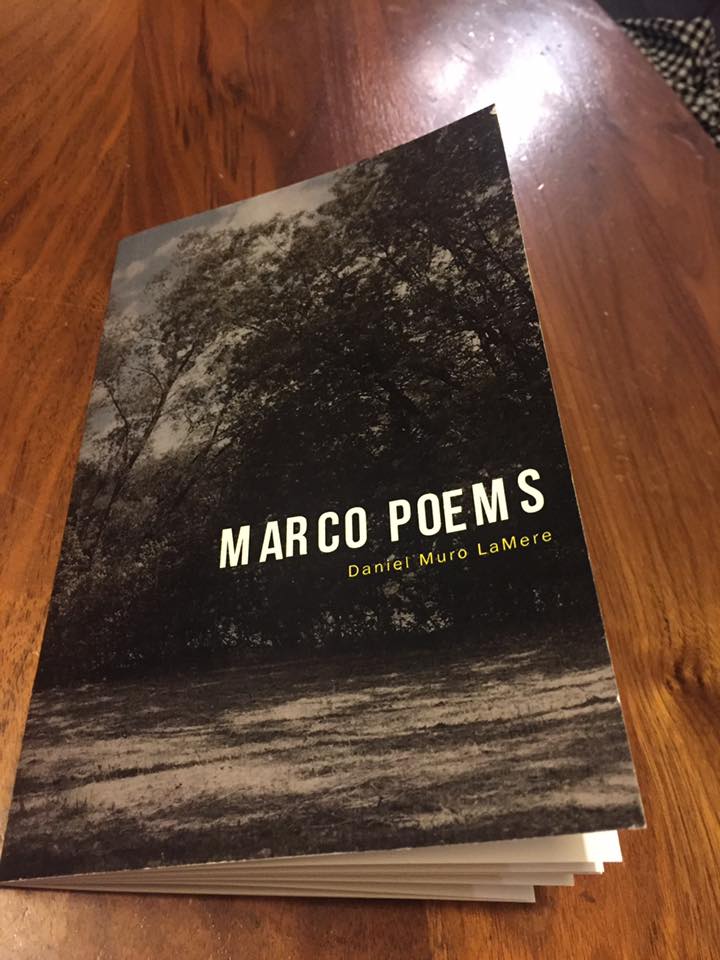

Hello, friends. The last three copies of my 2017 chapbook, Marco Poems, are currently available at the brand new and entirely lovely Comma, a bookshop in Minneapolis’ Linden Hills neighborhood (4250 Upton Avenue South). The owner, Victoria, is also the sole employee, and has been wonderful to me the couple of times I’ve been in there.

Also, as promised, a review of the chapbook, as written by a ChatGPT app I downloaded onto my phone:

“Marco Poems by Daniel Muro LaMere is a collection of poems that explore the themes of love, longing, and identity. Through his lyrical and poetic language, LaMere paints a vivid picture of a man in search of his true self. The poems are filled with imagery and emotion, providing a window into the struggles and joys of life.

“The collection is divided into three sections, each focusing on a different aspect of Marco's journey. The first section, "The Search," follows Marco as he searches for his true identity and purpose. The second section, "The Return," follows Marco as he returns home to his family and friends. The third section, "The Reflection," is a reflective look at the journey and its impact on Marco's life.

“The poems in Marco Poems are beautifully written and evoke a range of emotions. LaMere's use of language and imagery is masterful, and his words have a powerful impact.”

Sure, it’s not altogether factually accurate, and I may have nicked the idea to include an AI review from the Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend podcast, but there’s no such thing as bad press, right? Upon reflection (no pun intended), I maybe should have gone for three distinct sections mirroring the hero’s journey. Next time, I guess. Next time.

Anyway, it’s $6, signed and numbered. Tell Victoria I said thank you, and maybe by a sticker or something, too while you’re there, or a copy of Homie by Danez Smith, a superior poet by far (but please still buy mine, too).

They’re holding a rally to save

the anarchist bookstore that gave

our first glimpse through the mist

at the primitivists

and their sacred green and black star.

Tips from the collective cafe

are offered up to save the day.

This rickety altar

no rock of Gibraltar,

Hercules never stepped where we are.

And I can still see the scars

from all the uprisings

the bricks wear their char

but what’s most surprising

is the times they don’t burn

for the myriad spurned

and the beatings unearned

and the meetings that turned

as the white people yearned

to not be the ones that had so much to learn.

So they returned

to the ferns

at the top of the berm

upon which existential foundations stood firm

but the germ

that these terms

might be riddled with worms

like a sperm when it swims, it grew strong and it swerm

to a river of gasoline.

Try to discern:

when you try to transform how things are then they burn.

And so the third motherfucking police precinct did burn.

***

In the presuburban dawn,

the tranquility of a modest neighborhood

punctuated by ash

from the uprising,

from the righteous rage

of the streets it went up

rising on the wind

falling gently on edged lawns

thirty blocks beneath.

***

Everything is pulmonary.

Focus on the breath.

Bring your attention back to the breath.

Bring your attention back.

Bring your attention

to the knee that plunders oxygen

to masks from the pulmonary pandemic

into which are shot

chemical irritants, epithets and commands.

Bring your attention closely now

to the accelerants

ignited by the holy

or the outsiders

anarchists or white supremacists.

Cars without plates

and unsubstantiated online debate.

A last supper served four centuries late

and right here in the city that birthed you

the apostles are choking on curfew.

Paul Skye

When the North Loop was the Warehouse District

and Target Field a surface lot hemmed in

by train tracks not yet busy with Dakotan oil,

a gruff man with a Santa beard

pushed a shopping cart from his camp

on a forgotten loading dock

across cracked concrete and cobblestone

of forgotten streets

fertile with the blood of the 1934 Truckers’ Strike

and the Natty Ice that sloshed

from his ever-present Sprite bottle.

He used to sweep the sidewalk

in front of J.D. Hoyt’s

in exchange for Sunday brunch

with his family.

The sweetest goddamn thing you ever heard.

My co-worker found him frozen

in a bus shelter

across the parking lot

from his camp

under a timed out heat lamp.

2. Lowell

Before Rapson’s Guthrie was razed

and Nouvel’s ever more modern landmark

took its place on Mississippi's shores,

before Mill Ruins or Gold Medal Parks,

in the days before the razing

of Liquor Depot,

when Chaz would sometimes slumber

under the high voltage wires

and Dennis and Canada Dan camped

hillside beneath Minnegasco,

on the coldest nights there were those

who would seek shelter

in abandoned grain elevators.

One such man, Lowell, tall, thin, warm,

taught me to say Miigwetch, Ojibwe for thank you.

Lowell got himself in the Strib

after plunging to his death

one dark winter night

on stolen Lakota land.

3. Cerione

When Surly was not yet the moniker

of any local companies,

much less two,

when light rail seemed

an impossible dream,

a more tranquil University

Avenue.

More leafy places to make camp

near 280 and Kasota,

like the one behind KSTP

he shared with Charlie Buchanan

for what felt like a long time.

They called him Patch

or Irish,

and while it would be accurate

to call him a one-eyed

homeless

alcoholic

immigrant,

it would be incomplete

in equal measure.

He was the warmest man on the streets,

receiving guests and visitors

as if they were royalty

seated on thrones

of overturned pickle buckets.

Reach through decades for a snapshot

of a memory

of a dog.

Was there a dog?

Didn’t he love her?

Didn’t she die?

He drank and wept and drank some more.

And when he went,

the Whiskey Johns and

Charlie Buchanans of the world

were left to tramp alone,

the ache of that son of the isle

caught in their breath.

4. Elf

Before the city and Covid-19

labored to close the Hard Times,

it was hard to discern

who was unhoused

and who were the real denizens

of that West Bank institution.

Give Elf a sandwich at lunchtime,

see him rolling cigarettes that evening

at a table near the window

arguing with anyone about

whether or not Greg Ginn mattered.

Like any of us,

he might have been so many things.

he might have been a predator,

for as much as I could tell.

Nowadays his photo

adorns the wall of the dead,

not far from the painting

that Sally made of Gordy.

5. Wind Tunnel

In the days when Minnesota forbade liquor

stores from selling on Sundays,

the most chronic alcoholics

drank Listo..

Roll up on them in August

near the old VFW on Washington

or the train tracks over Broadway,

scent of mint and sick

while best friends play blind detective

to ascertain who punched who last night.

Hard livin’ on Sundays

and collecting cans for cash

for the old Jug Liquor store.

Before Scotty and Grandpa

had the deal with the junkyard owner

to stay in that camper,

the owner of the Jug

let Scotty spend the night

in the aisle.

Scotty was a juicer, but not a thief.

and the owner must have been a stand up guy.

Behind Stand Up Frank’s

in the alley next to the auto warehouse,

names etched in soft brick.

All that hard livin’, how many could be left?

That guy named John they called Kaw-liga

after the Native guy in the Hank Williams song?

My name is there, too.

6. Hello in the Camp

All of these now gone,

people who insisted on being people

before it was allowed,

when cops rolled camps to move you on

without hesitation.

In those days they left you

with the clothes on your back

and the Louis L’amour novel

in your back pocket.

This was back before

we ever considered

whether their services

were even necessary,

Before Jeff started manufacturing

hand-washing stations

Before the Park Board said

welcome

feel free

to use our grounds

to gather your dignity.

Before they doubled

back

and started rolling

folks

again.

My dad’s youngest brother worked

construction jobs except for when he didn’t.

Inhaling tar, particulates, layoffs.

“Garage Night” with the boys on Mondays,

inhaling watery beers by the case,

activating my folks’ muscular scorn.

I inhaled their judgment on car rides home,

upper midwestern northern european

passive aggression and shit talking.

At forty-four, I long for a Garage Night.

Less for Milwaukee’s Best than to commune,

wringing what joy one can from finite days.

Half my life ago, brain still underdone,

evangelical, undiagnosed

rejection sensitive dysphoria.

Poor proselytizer, then, preferring

passive to aggressive, opting instead

to leave people alone.

Unless they were supine, I guess,

inhaling hospitalized air through

clear medical grade PVC tubing.

None of this duplicity conscious,

boarding the 14 to North Memorial,

Gideon bible in tow.

Concession: none of us knows how to grieve,

to visit those sentenced to perish,

the small talk of final encounters.

Rejection sensitive even then,

no Godtalk breached the transom of my lips,

altar call scrawled instead in the front pages.

I don’t think God is real, nor heaven.

Life is vapor, mysticism on the air.

Tom was fifty when he last inhaled.

How many feet per second did your thoughts

fall through your skull midair preceding loss?

Fall prey to things we wish that we had done

like caring for the sick? Is that too fraught

with politics? And so instead we shun

the ones who need us most, two separate sons

both failed by us while up on that third floor

now we all feel a grief I can’t outrun.

The marble floor transformed to site of gore,

onlookers, we who heard, left to implore

the whims and wonders of a sunless sky.

He did a thing that sanity abhors.

At Shake Shack with my family there’s a guy

there with his daughters, then I see his eye

transfixed. The local news is on the screen

above our heads. His face is asking why?

And now the news says Landen is between

two worlds. He’s helped by doctors and machines

Emmanuel will now be thrown away

as some among us long for guillotines.

If only we cared as much as we say

we would have taken action on the day

we saw something was wrong, wellness betrayed

by our allegiance to naivete.

The 2040 Plan at the Wall of Forgotten Natives

No yard signs

in opposition

to Minneapolis’ aggressive

affordable housing plan

along Hiawatha Avenue,

just dozens and dozens

of tents

and an old woman

along that avenue named

for a distant tribe,

sitting on unceded land,

wrapped in a blanket

against the chill

of the coming winter.

From now until the end of the year, the Marco Poems chapbook will be discounted from $6 to $5 each, with 100% of that money going to The Coalición de Boricuas en Minnesota. We can all do a little bit of good together when we try to. From The Coalición de Boricuas en Minnesota's Facebook page:

"The Coalicion de Boricuas en Minnesota formed immediately after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico Island. The coalición is form by a group of professionals in Minnesota whom are Puerto Ricans and have family on the Island.

"Funds donated to la Coalición de Boricuas en Minnesota are collected and distributed by ImpactLives™ a non-profit organization 501(c)(3). Funds will be used to respond to the immediate and urgent basic necessities of those affected by this natural disaster."

* * * * * * * * * *

I sent Aaron Cometbus a copy of the chapbook a while back, since his zine is mentioned in one of the poems. At some point since I received a mangled reply that was damaged in transit and then sat with a bunch of other mail in a tray until I discovered it today:

WE CARE

EUREKA

"It captured som--[unintelligible]," raves Aaron Cometbus!

braggadocio to let you know

This is a Drone not Drones poem,

a making broth out of bones poem.

A poem so fresh it probably never had a home phone.

Peace summit at the Pizza Shack with Vice Lords, cops and Stones poem.

A Yanez verdict burning straight up systems overthrowing poem.

This shit’s self published and collected in its own tome.

This poem’s grown.

It groans, moans.

A bright light shone on all the places where you won’t roam.

Dig a little deeper and discover that this loam’s foam.

You’re thrown, holmes.

Your seed sewn.

Put your ear to the universe and listen to this poem’s ohm

vibrating tectonic plates till we’ve all got our own thrones.

So, that's actually a sticker idea I'm toying with, but then I don't know if any of you guys actually exist and/or would buy one, so let me use this opportunity to also mention that Marco Poems, my debut chapbook/zine situation, is now available at Moon Palace Books in Minneapolis. This in addition to its availability at Minneapolis' Boneshaker Books, this website, or from me in person. If you would like to distribute via your own store, record label website, or fanned out on your band's merch table, please get in touch.

But it did make me think about how, when we try to communicate with The Others, we do things like sending gold records into space.

Sometimes I wonder if these blog posts are gold (silver?) records that I'm sending into space.

And while that may absolutely be the case, it is also possible that all the space records get intercepted. Maybe it's 2078, and despite every medical advancement, I have somehow perished, but somehow the internet has persisted, and you, dear reader, have discovered this site.

First things first: congratulations.

It seems only fair that you should be recompensed for your efforts. I offer you, below, the poem "Hole in the Wall" from my inaugural chapbook. Please, if you don't already have a copy, get in touch with my estate and demand that they sell you a copy. Lord knows those bastards are probably making a mockery of my legacy.

The Hole in the Wall was a real place, located in what used to be called the Warehouse District of Minneapolis, but, through the miracle or realty is now known as the North Loop (because it is just north of downtown, presumably, but I can't for the life of me understand why it's a loop -- this is not Chicago). It was an actual hole in an actual wall along the railroad tracks that abut downtown and head west to Willmar and east to Somewhere Else.

In its day, as I understand it,. the Hole in the Wall was a famous homeless camp for the sorts of made-classy-by-history railroad tramps that likely frequented the nearby skid row (itself a casualty of 1960s urban renewal).

I got these stories as hand-me-downs when, at 18, I was working for the Salvation Army out of its Harbor Light shelter on a truck that delivered sandwiches to those homeless citizens who didn't want to come in to the shelter (and in those days, at least, I can't blame them -- it was chaotic there at best, and I didn't ever really feel too safe there). It was a hard spot to access by truck, as I recall, and so we didn't go there too often, and, on many occasions, struck out when we did.

But then we heard about a family who was staying there, and we visited them a handful of times, delivering sandwiches and whatever else we could. I don't remember much of those visits, except that there were kids, and a mom, and that everyone seemed generally on edge, furtive even. I can't blame them.

Twenty years later I'm almost certain that the Hole in the Wall has been razed,.sealed off, or otherwise been made inaccessible by the construction of Target Field and the march of progress. It's a difficult internet search, too, for what was purportedly such a famous homeless camp, but the one link I did find features a guy I knew back in those days from another camp.

I should also acknowledge that the poem features another character from the streets, Thumper, who was a real person. Her real name (if she and/or my memory are to be believed) really was Diana, and if she's still out there somewhere and ever has occasion to do so, I hope she'll forgive me for taking liberties with her story here. I don't know if she ever camped at the Hole in the Wall.

I also want to say that, while the paint huffing part is not fiction, Thumper was extremely kind, exuberantly so. It is not my attempt to demean her in any way, only to shine a light on realities that I think many of us would prefer forgetting.

Hole in the Wall

You meet all kinds of people on the streets —

One Thumper, nee Diana, flecked with gold,

The remnants from her favorite way to fly.

That week that Marco spent with her in camp,

Along the railroad tracks outside downtown,

A place those in the know just called “the Hole,”

was six days longer than he’d planned to stay.

The holidays had brought him low again,

to drugs, to sex, to life away from life.

A place has never been more aptly named;

a wall, a hole, a cellar long forgot,

a world apart, lived mostly in the dark.

They’d met at Harbor Lights in line to eat,

scored drugs from someone she knew at the desk

and walked the railroad line back to her “place.”

They’d both smoke crack and she’d huff paint all day,

and here and there they’d find the time to fuck,

and that’s how Marco spent his lowest week.

and its noon

or its midnight

or its thursday

and with every inhale

every droplet of perspiration

beading

pregnant on the brow

and thumper pregnant too

the immateriality of time made manifest

beneath warehouse district streets

tasting the darkness marco is green

stealing the last of the holiday decorations

from his souls interior

and little cindy lou who

cheek smudged with dirt

books in her hand

coming or going from school

through the hole in the wall

and marco didnt know there were kids

he didnt know who was there

in the haze of no light

forms in the dark

rodents and humans and ghosts of each

mythological conflations of the two

he didnt know and then he did

and what the fuck and hes green and

the contents of his stomach present

themselves at the girls feet and

marco is out

out

out

out of the hole and

running

sweating

running

freezing

at the river

at the trestle

and almost over

almost over

almost over

marcos lowest week is almost over

I'm so pleased to announce the publication of Marco Poems, a chapbook almost two years in the making. Click on the "Buy Poetry" link above to purchase your copy directly from me. $6 gets you what I think is a beautiful little book, 8.5 x 5.5", signed and numbered just this evening by yours truly. This has been a labor of love, and while the DIY aspect has made my brain ache at various points along the way, I'm thrilled with the end result.

Just a reminder that yours truly has an essay in this upcoming book! Order yours today!

Hey friends, it's been a while.

A few quick items:

1) You can preorder your copy of Rad Families: A Celebration from PM Press, a fantastic radical Bay Area publishing house whose entire catalog is worth perusing. I'm honored to be included.

2) I have a finished manuscript, tentatively titled Marco Poems, a mini-chapbook with about fifteen pages worth of writing. The hope is to collaborate with some artist friends and self-publish something really beautiful that you can hold in your hands. If you'd like to contribute a giant (or even medium) bag of money to that end, I'll allow it. In the meantime I'm shopping it around to publishing houses, but that length is kind of weird, so we'll see. If you are a publishing house and you want to take a chance on this project, get in touch.

3) Some of you will remember that I'm a teacher. As the school year winds down, and summer looms, the time available for me to give to creative pursuits begins to increase somewhat, which is to say, watch this space for more art.

Image courtesy Ted Hall Photography

Note: For the sake of confidentiality, I’ve omitted some of the names of the subjects of this piece, including only what has already been reported elsewhere. Additionally, this piece originally appeared at the Minnesota Writing Project's Urban Sites Network Blog, which I help operate.

While I love teaching, there is, at times, an emotional weight that comes with it that I couldn’t even begin to try to describe to those outside of the profession. These last days of 2015 have produced grisly news headlines whose subjects intersected with my life as a direct result of me being an educator: this one murdered by police, that one beaten and hospitalized by his students, another charged with murder and aggravated robbery; the latest additions to a pile of similar headlines that have touched me over the years.

I began my career in education in the spring of 2005 working as a paraprofessional at Harrison Education Center, a federal setting IV facility for students with emotional and behavioral disabilities (E/BD). I was 27, a student at Metropolitan State University’s Urban Teacher Program, and eager to get my foot in the door in a public school.

I was also in completely over my head.

I figured I could handle the E/BD part — I was coming from a day program for adults with developmental disabilities where human bites were a hazard of the job — but this place was absolute mayhem.

The administrative style could best be described as laissez-faire, ill-advised under the best of circumstances.

These were not the best of circumstances.

A word about E/BD for the uninitiated, and please note, there is an awful lot of my own opinion seeping in here: E/BD is solely an educational disability, which is to say that you could receive the label of E/BD from a school but not be diagnosed with any sort of other real and actual medical disability. Ostensibly, the idea is that your inability to regulate your emotions (and subsequently your behavior) is a barrier to the education of yourself and/or your peers. It can look a lot of different ways, does often accompany actual disorders (Oppositional Defiant Disorder is a big one), is far more subjective than many would like to admit, and is, as a result,given disproportionately to African-American males.

As for the settings, setting IV means 100% of a student’s day is spent in special education, so a federal setting IV high school for students with an E/BD designation means a lot of locked doors, and a lot of students who were deemed unable to make it in a more mainstream setting.

It was, as I said, chaos.

I learned a lot, mostly about gangs, about how to and how not to talk to students when they are escalated, and about injustice. Sadly, the students weren’t learning anything. The worksheet was king, particularly the word find. I vowed in those years never to assign a word find for any reason. (So far, so good.)

The next year the head of special education for Minneapolis Public Schools took the school over. He restored order, relative to what it had been, and insisted that teachers actually teach. Things were better, functional even, though I’m pretty sure no one was ever asked to write a paper in the time that I was there.

During that time I met Jamar Clark. He must have been about sixteen, and while he did at times display an explosive temper, he was mostly quiet, with a mischievous sense of humor. As these things go, I only remember a handful of things about him really well: 1) I remember his face. He had an incredibly expressive face. A quick google image search of his name yields a lot of images that aren’t him, but the ones that are display a range of disparate emotions. 2) I remember he had a slight speech impediment. Or at least I think he did. 3) At the very least he would adopt this kind of funny voice when we’d get to one of Harrison’s many locked doors, saying “No more locked doors.” It’s loaded with meaning now, but at the time it was a funny quote from Next Friday (I had to look that up just now). 4) I remember sitting in the computer lab with Jamar and some other students. I was at the computer to the left of Jamar, who was so jazzed about the upcoming release of Li’l Wayne’s Tha Carter II. There was an innocence in how giddy he was that makes everything that happened since all the more tragic.

Or maybe it’s everything that happened before. Others have written better than I could about the conflicting forces pulling Jamar in different directions, using safe and unexamined phrases like “troubled past,” and that’s fine, but what are the forces outside of oneself that cause one to end up at a high school where no one is assigned any papers? Or, if we take that as our starting point, if we’re really honest with ourselves, what kind of outcomes do we expect for someone coming out of such a system?

Or, to really put all of my cards on the table, given the value that we as a society have (or have not) placed on this one life through our education system alone, whywouldn’t I expect that he would be murdered by police*?

And the news cycle continues, and it isn’t long before a former colleague from another district is sent to the hospital after trying to break up a fight in the cafeteria. People ask me, “what’s going on over there?” and I opine, letting myself get fired up about how district policies that lack restorative practices create an unsafe environment for everyone. “The thing is,” I attempt, “I feel as badly for those kids as I do for that teacher.” They look at me aghast. “How do you get to a point where that’s okay? Where did we fail?” They don’t know. Neither do I.

And then another headline. Another former student, this time part of a violent crime spree one fall night that included credit card theft, home invasion, and murder. I remember this student well, too. His hands trembled and he had long fingernails. His attendance was terrible. He may have been on house arrest at one point and worn an electronic monitoring device on his ankle. I remember watching him flirt with a girl in the gym, calling her “Shawty,” smiling wryly. Better than his nickname, I suppose: “Poopy.” I remember we had to watch him closely in the gym, something to do with his heart.

I read a statement in the newspaper that he had given to the police when charged, stating that “only intended to do robberies and that he was upset that people were getting killed,” and I guess I believe it. I also believe that it doesn’t matter, that his fate is sealed, and maybe was long before that night.

And the thing I absolutely don’t know how to explain to non-educators in my life is that, in truth, I have no idea what to do with any of this, but I move on because I have to. I write this post. I think about how I’ll supplement Native Son when I begin teaching it next month to include a challenge of privilege and a pedagogy of resistance. And I hope like hell that the news will give me a little peace, because I have plenty more Jamar Clarks I’m worried about.

*I want to acknowledge that it took me the better part of a week for my feelings to coalesce around this issue. Having written angry poetry in the wake of Treyvon Martin, Mike Brown, and Sandra Bland’s extrajudicial killings, I would have thought I’d know exactly how I felt if something like this happened in my city, to someone I knew. But I waffled. I offer that because our human reactions to things like this — things I suppose none of us should have to deal with — are very complex. The politics of proximity, I guess. The other day a friend referred to Jamar saying “sounds like he was a piece of work,” and I bristled, explaining that I’m too close to the situation to say that. But like so many of us, she was trying to make sense of the senseless, and that’s where she ended up. It’s complex.

Banner images provided by Classic Sailing or GollyGforce, for demo purposes only. Powered by Squarespace